One of my dissertation readers was a professor of Italian named Elena Coda who I had asked to be on my committee without us ever having had a class together. Surprised, she explained in her forthright way that she had no idea who I was, but that my project sounded interesting and would I care to stop by her office hours one day to talk it over.

I was happy she was considering it and so, one afternoon, I walked from State Street north up the Memorial Mall toward Stanley Coulter Hall where her office sat in the back of a hallway that encircled a large central auditorium. The office was brightly lit by natural light and had a little of that wood-feeling academic atmosphere that was given away only by the fluorescent light fixtures — turned off — which were covered by the flimsy, textured plastic associated with institutions, and the floor, with its occasionally cracked speckled tile you could slide the chairs across.

We talked about Modernism, since that was ostensibly the reason I had sought her out, and she was upfront that I would have to take her European Modernism class in the next term if I had any hopes of her being on my dissertation committee. We talked about place, the topic of my philosophical research, and I explained the basic currents I followed from Edward Casey’s book, Getting Back Into Place.

She began recommending books. I had just finished a course on James Joyce’s Ulysses and the term paper I wrote for that class ended up being my first academic publication, in College Literature. She told me, if I hadn’t, I must read The Man Without Qualities, which she introduced by its German title, Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften. It was, she said with a smile, the first novel published after Ulysses. She was an expert on Italo Svevo and Luigi Pirandello, an astute student and critic of psychoanalysis, with an eye for how our own times resonate with the themes of fin de siècle hand-wringing about cultural decline and degeneration. She would have me read Nordau and Weininger. She had a lot of questions for me about Heidegger.

Speaking of place, she said, you should read Danube, by Claudio Magris. And I did read it. It was, perhaps, one of the more perfect book recommendations I had ever received. The book meandered, like the river it described, coursing along seemingly unrelated territory, unrelated except for the immanent place of the river and its history.

Places, Ed Casey argues, are always cultural. They have a history. This is, in part, because places are where people exist. We need a place to be. And so we make it.

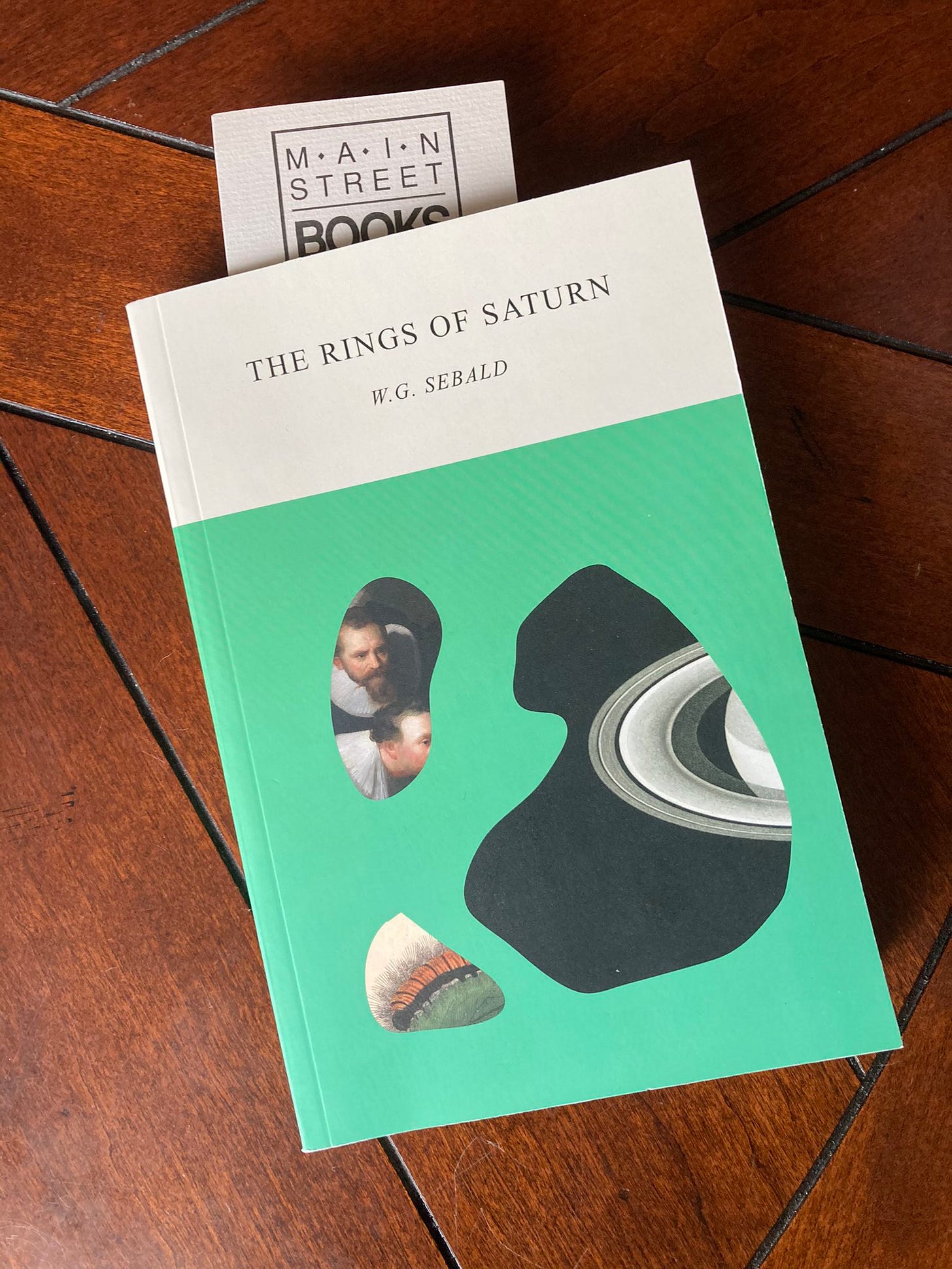

It was Danube, ultimately, that carried me on its winding way to W. G. Sebald’s strangely beautiful travelogue, The Rings of Saturn. Every time I mentioned Danube, if the person with whom I was speaking had read Rings of Saturn, they would recommend Sebald’s book without fail. This happened several times. Finally, Ryan Ruby would hand me the proverbial straw and my camel collapsed. I bought a copy of Sebald’s modern classic at Main Street Books in Frostburg, Maryland and eagerly sat down that evening to begin.

It is appropriate that a book often alleged to be a study of “England’s imperial past [sic]” begins with the narrator, perhaps Sebald himself, waking from a period of convalescence and taking stock of the world around him. I imagine many in England would like to wake from the fever-dream of imperialism and find themselves somehow refreshed and disburdened, finally absolved of a historical sickness that continues to haunt their memory.

Imperialism is far from over, of course, and however one wakes in the morning, one is still awakened to a present in which the actions of the past have taken on the air of objectivity and formed an unrevisable point from which we must move forward, the image of that static past remaining, however small, in the rear-view mirror, a permenant part of the background.

This is how Sebald approaches the history of coastal East Anglia and its ties to imperialism past and present. There is a smart distance to the writing that allows the objects of history to appear as just that — objects. But we are never too far, in the midst of all this objective description, from a sudden plunge into the depths of normativity. Sebald, however, never offers us ethical digressions that serve didactic purposes. There is never really a sense that Sebald has come right out and said, “this was wrong.” But there is a sense that it has been said nonetheless, and perhaps it has, in so many words.

More than anything, I found myself being taken away, almost immediately, from the blurbs, the expectations, the interpretations and heuristics that frame Sebald’s work as critical or clinical and was just following along, meandering with the author along old and new paths, through the country side, captured for a moment by this locale or that, stopping for a tea, for a rest at a local museum, for a chat with an old gaffer responsible for the marginal upkeep of some near forgotten estate. What I read almost defied interpretation. Or, rather, it seemed to interpret itself, to suggest what was just coming around the bend without fully revealing it.

Oh, I was jealous!

How does one write like that? I though of the old Isaac Babel line about Tolstoy — that if the world could write itself, it would write like Tolstoy. Perhaps not the world, then, but just the East of England? It practically short-circuited my critical faculty. Couldn’t I just coast along like this indefinitely?

But then the old doubts come back… Am I really so bourgeois as to settle for this oblique critique?

I think I am, for the picture of Rings of Saturn as a reflection on England’s imperial past is incomplete, just as Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften is only partially about the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the party that never arrives.

The rings of Saturn are made of dust. Well, cosmic dust; most particles measure between one centimeter and ten meters. It’s mostly water. The rings are constantly in motion, shifting, larger accreted structures forming and falling apart. The rings of Saturn are a process of formation and decay.

Perhaps Rings of Saturn is about decay. If it is, then formation cannot be far behind. If, on the one hand, Sebald writes of a decaying empire, he is also writing with the other hand of a formation that is at once a personal memory and something more, something public. Yes, memories decay. Like the recurring drama of Thomas Browne’s skull and the development of his natural philosophy, the memories of the past themselves decay, just as nature itself is slain in the writing of natural philosophy. But their decay, insofar as it is recorded, constitutes in the act of negation also the formation of a new memory, of a new document, of a new historical object that appears in the eye of the present and gives the new times their meaning, significance, and trajectory. It could be that this is the dialectic, the superficial contradiction between historical discontinuities and the sublated continuity of these discontinuities in time.

Sebald writes an empire in decay, but that is not all. In this writing, there is something nascent, without a word. This something is a wordlessness for what comes after the fall. It is a silence that cannot be articulated because it is the future and articulating it beyond mere possibilities would mean its annihilation-as-the-future in favor of what can be said about the present.

“Tell me more, Aunt Ashburnham, please tell me more,” Sebald puts these words into the mouth of a hand-wringing boy from a Swinburne painting just before climbing to Dunwich Heath, “forlorn above the sea.” We are always asking for more and somehow getting it while still being denied the explicit analysis our more scholarly instincts demand. And all for the better! How often I’ve wanted to deny that pesky pedant in favor of poetry — and how well Sebald achieves this poetics without sacrificing realism on the alter of the symbolic.

If there is a fault to Sebald’s work it is perhaps that he is too consciously aloof — that he has lost himself so fully in the writing that he has forgotten that he is lost and so acts as if he remains outside of what is all around him. We are never quite sure of the position of the text, if it is indeed critical, if it is simply a documentary, if it is somehow complicit.

But dammit, maybe that’s just what we need. In a time where criticism is conflated with public relations, or advertising, overly fawning press releases for the work of our friends, or else polemics reign and we have nothing but dunks, hot takes, and the unforgivable snark of someone who cannot be bothered to care that much about art.

I thought that Ryan Ruby, who ultimately tipped my hand toward The Rings of Saturn, had said that Sebald trusts his audience. I went back to Twitter, searching for this memory that had become real for me. I could not find it! Ruby himself joked with me that he didn’t recall saying it. That’s funny. It’s funny because it’s true, isn’t it?

I felt that Sebald relied on me to piece things together, that the techniques of realism had succeeded in placing the pieces in my hands and gesturing toward some final form. But if i wanted to see it, if that picture in words were to appear to me in its fullness, I would have to put them together. It would be up to me to close the gaps between the dust particles that make up the rings of Saturn so they would at last appear solid and whole. But he would never let me forget that this was my construction.

Sebald would remain, winking in the wings even while the show was going on. All this seeming and longing in just a short time. A few sessions and the book was over. I hadn’t even begun to think about the images, the sketches, photographs, and grainy facsimiles that accompany the text. At first blush, the images lend credence to the objective appearance that history takes on thanks to the miracle of hindsight. What is so difficult and ambiguous when one lives it becomes painfully clear and determinate in hindsight. A veritable transubstantiation. Their degraded appearance on the soft pages of the book, the lack of color, the cloudy, indistinct character this reproduction transmits is another instance of decay that, at the same time, constitutes a new angle on the place. Also, by their incorporation into and accompaniment by the text, it is suggested that a synthesis has taken place, and these fragments have been brought into a unity that hides their particularly degraded qualities if one does not pay attention to them.

I hardly want to leave readers here, believing Sebald an ironist. It takes a certain earnestness and fidelity to the thing-in-itself to describe the autumn leaves, the way they were on Purdue’s campus as I walked from Stanley Coulter, around the corner, a 19th century brick facade on one side and a tall, narrow scultpure of a No. 2 pencil leaning away from Beering Hall ahead. At the end of my meeting with Coda, she laughed. We’ve talked about this for over two hours, she said. You know I’m going to be on your committee. I’ll see you in European Modernism in the Spring.